Rust has many ergonomic features that make common patterns simpler, but can also cause confusion because they increase the inconsistency of the language, or feel counter-intuitive in some cases.

Consider this code:

use std::rc::Rc;

fn main() {

// A new `Rc` has a count of 1.

let a = Rc::new(());

assert!(Rc::strong_count(&a) == 1);

// Calling `a.clone()` uses the `Rc::clone` implementation

// and increments the count to 2.

let b = a.clone();

assert!(Rc::strong_count(&a) == 2);

// Calling `(&&a).clone()` uses the `&T::clone` implementation

// and the count is unchanged.

let c = (&&a).clone();

assert!(Rc::strong_count(&a) == 2);

// What happens when we call `(&a).clone()`?

let d = (&a).clone();

dbg!(Rc::strong_count(&a));

}

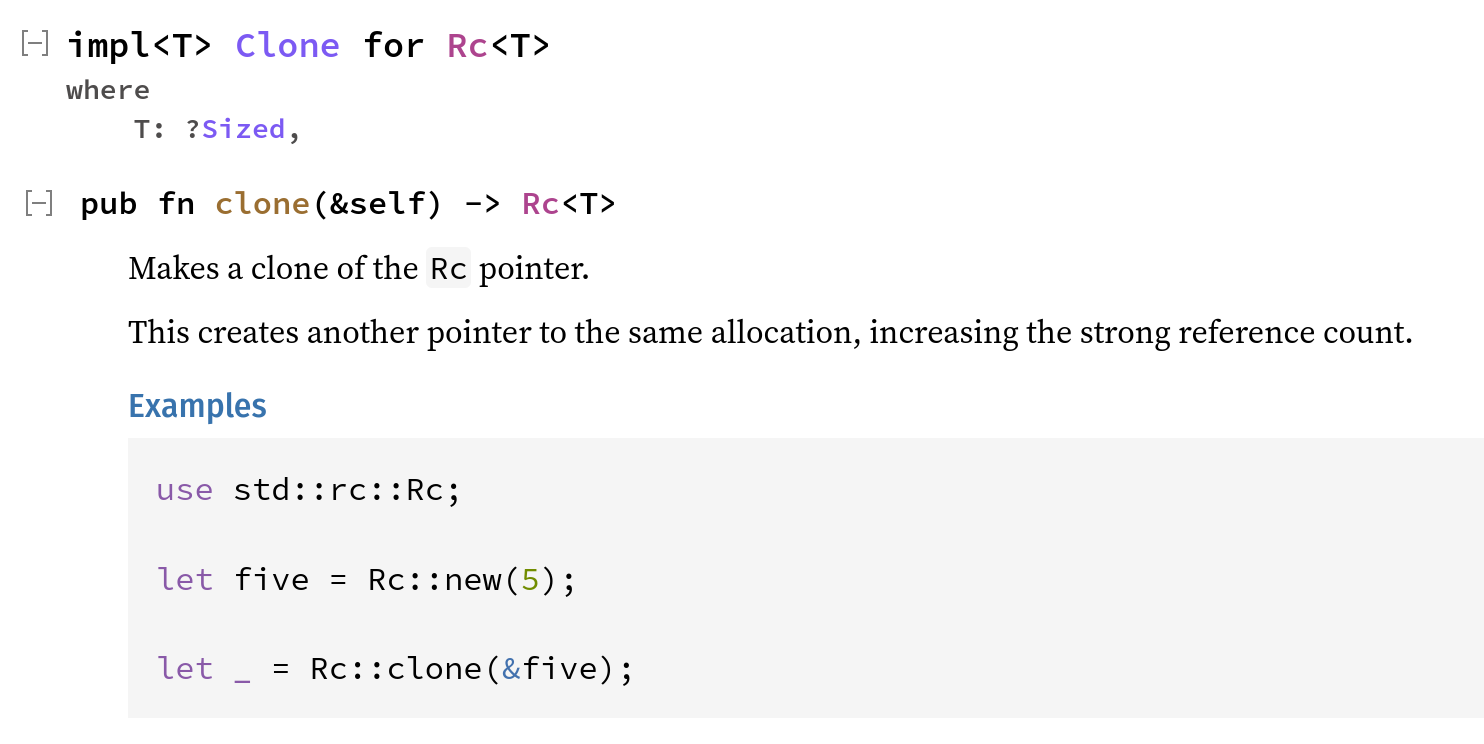

The Rust reference counting type Rc implements the Clone trait. Every call to clone increments the strong count for the Rc instance. This allows us to count how many times Rc::clone has been called.

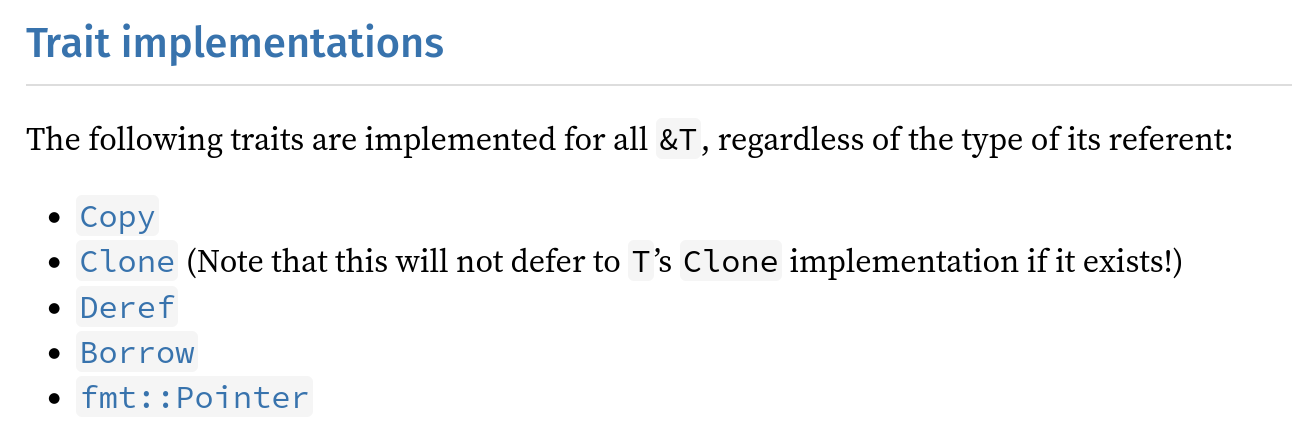

The Rust shared reference type &T also implements the Clone trait. (T can be any type including Rc). Note that the documentation for &T points out that “this will not defer to T’s Clone implementation”.

The receiver for a method is the expression before the dot. With a.clone() the receiver is a with type Rc<()>.

The reference count increases, showing that we called Rc::clone.

// Calling `a.clone()` uses the `Rc::clone` implementation

// and increments the count to 2.

let b = a.clone();

assert!(Rc::strong_count(&a) == 2);

}

With (&&a).clone() the receiver &&a has type &&Rc<()>.

The reference count does not increase, showing that we did not call Rc::clone.

We called &T::clone instead, and that does not delegate to Rc’s Clone implementation.

// Calling `(&&a).clone()` uses the `&T::clone` implementation

// and the count is unchanged.

let c = (&&a).clone();

assert!(Rc::strong_count(&a) == 2);

The question is what happens when we call (&a).clone()?

let d = (&a).clone();

dbg!(Rc::strong_count(&a));

The receiver has type &Rc<()>. This type does not match Rc<T>. It does match &T, where T is Rc<()>.

The intuitive answer is that (&a).clone() calls the &T::clone implementation, the count remains unchanged, and the code prints Rc::strong_count(&a) = 2.

But running this code prints Rc::strong_count(&a) = 3, showing that it does, in fact, call Rc::clone.

When you look at a Rust impl block, such as impl<T> Rc<T> {}, it appears to implement methods for a single (possibly generic) receiver type (Rc<T>), and the different forms for methods (self, &self, &mut self) indicate how the receiver is borrowed in the method.

However the self argument to the method plays a more significant part than expected.

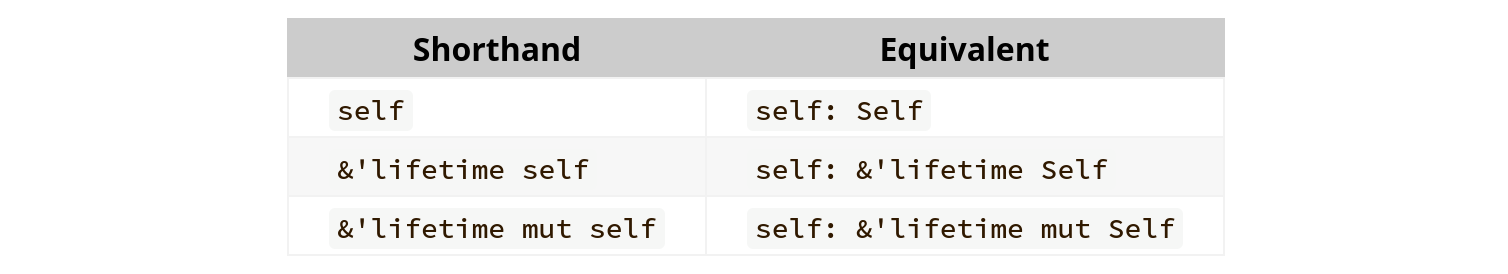

First, it’s useful to know that the ubiquitous method parameters &self and &mut self are syntactic sugar to combine a parameter called self with the parameter’s type (another ergonomic feature that increases inconsistency, but simplifies a common pattern):

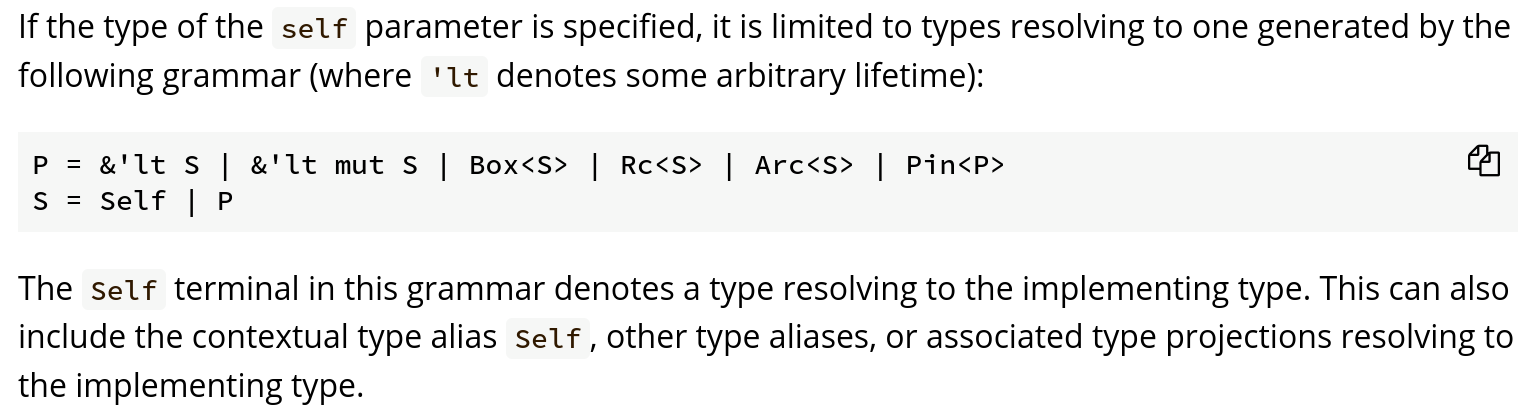

This helps understand this section of the docs:

What this means is that an impl block can define methods for multiple types. These types are related to the type named in the impl block. For example, an impl<T> Rc<T> block can define methods for Rc<T>, &Rc<T>, &mut Rc<T>, Box<Rc<T>>, Rc<Rc<T>>, Arc<Rc<T>>, Pin<Rc<T>>, and also combinations such as &Pin<Box<Rc<T>>>.

The Clone trait defines the method signature fn clone(&self) -> Self, shorthand for fn clone(self: &Self) -> Self

When Self is Rc<T>:

impl Clone for Rc<T> {

fn clone(self: &Rc<T>) -> Rc<T> {...}

}

The implementing type is Rc<T> but the method clone is implemented for the associated type &Rc<T>.

So Rc<T>::clone gets called when the receiver is &Rc<T>, including for &Rc<()>.

Similarly, impl<T> Clone for &T implements a clone method matching the generic type &&T.

impl Clone for &T {

fn clone(self: &&T) -> &T {...}

}

So &T::clone gets called when the receiver is &&T, which includes &&Rc<()>.

Note that there is no clone method for the type Rc<T>.

So our question above was misplaced. It is not why does &a.clone() call Rc::clone.

The real question is why does a.clone() call Rc::clone when Rc<()> does not have a clone method?

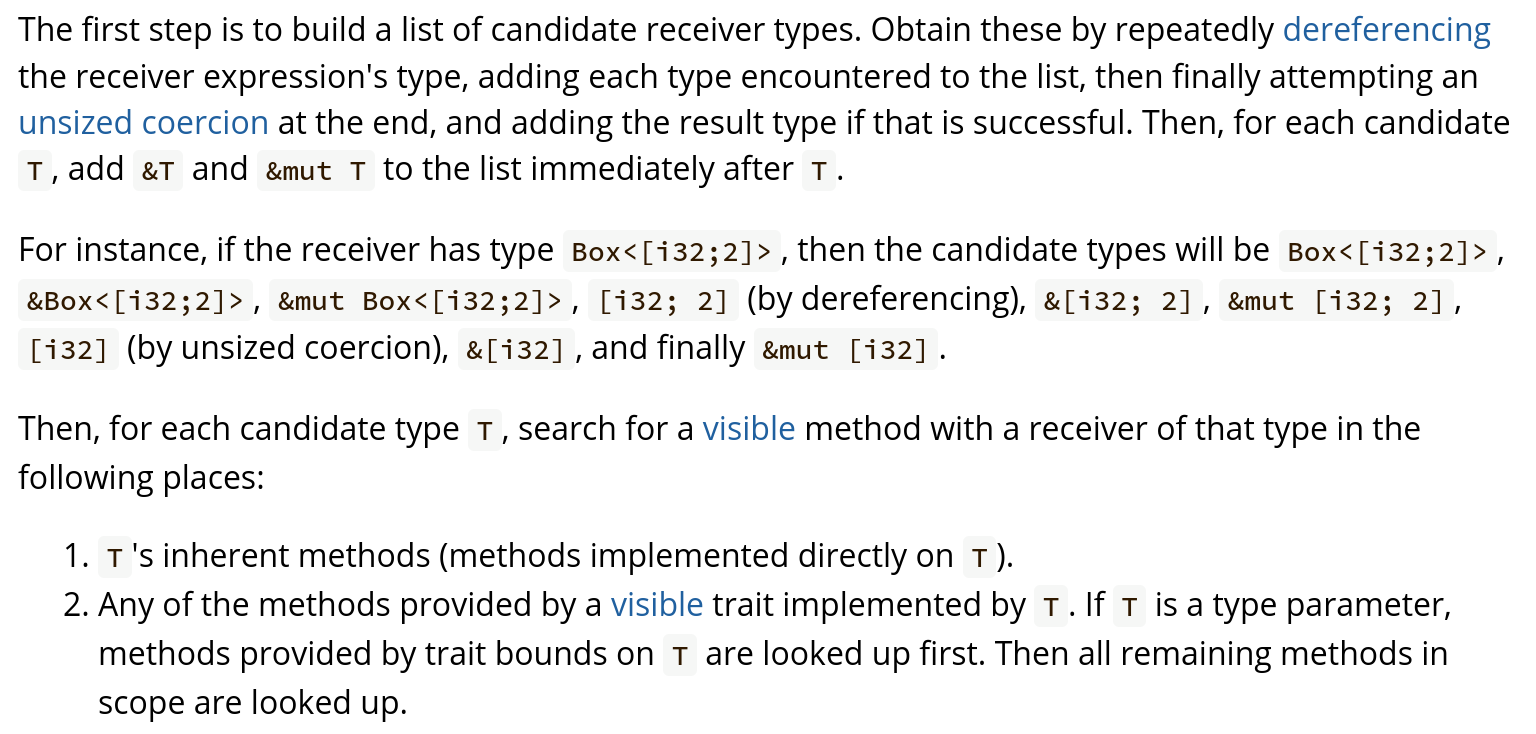

a.clone() works because Rust uses a procedure that matches methods against a chain of types derived from the receiver.

For Rc<()> the chain starts Rc<()>, &Rc<()>, &mut Rc<()>, and then continues through Deref to (), &(), &mut (). For each type in the chain, Rust looks for a method that matches.

For a.clone() the first candidate, Rc<()>, does not match any clone method. So we move on.

The second candidate, &Rc<()> matches the Rc::clone implementation. So Rust stops here, creates a reference to the receiver, and passes that to the Rc::clone implementation, incrementing the count to 3.

Some more examples of this confusion around references and method resolution:

If my example has too much reference counting and not enough dogs, then this

users.rust-lang.orgpost is for you!The docs above describing the creation of the chain also describe a preference for inherent methods (defined in an

impl Typeblock) over trait methods (defined in animpl Trait for Typeblock). See thisusers.rust-lang.orgpost for an example where this is relevant. Both methods in this post have aselftype of&Foo. Hence they are at the same position in the chain, and the inherent method wins.

Note that the common pattern for confusion here is expecting method resolution to proceed using the implementing type named in the impl block rather than the type of self in the method.

The key to understanding method resolution in Rust is:

Know how the candidate chain is created from the receiver type in the method call.

Look at the type of

selfin each method rather than the implementing type named in theimplblock.